Boxer’s First Case

Anyone trying to escape the landlord will move out in the middle of the night. But not Boxer. He was not escaping. He was arriving. He moved into the house next to mine in the middle of a warm July night.

A poet’s wife living nearby had had a noisy party, going well past the curfew hour, and I had shut all my windows. That was when Boxer struck, or landed his blow, so to speak.

Around ten the next morning, I was sitting on my front balcony, reading the newspaper and having a coffee, when the balcony door next to mine opened, and Boxer stepped out, smoking a thin cigarette.

“Ah! My neighbour! Good morning to you! I’m Boxer.”

“Oh! Uh – Mr Boxer, my name is — “

“No, no – just Boxer. Let us be informal.”

“Boxer, yes. I’m Charles. Charles Ross.”

“Charles. Let us pretend that this iron fence does not exist between us, shall we? Very sharp, these points. But in an emergency, please, do not hesitate to climb over if you urgently need to seek my help.”

“Thank you! But, well, I doubt I’ll have to. At least I hope not.”

“Could you tell me, Charles, when the post arrives? Or has it already come?”

“Probably in a few minutes. See down there, in that side road? When you see the postman there, it’s exactly another half hour before he reaches us here.”

“He must make a wide arc, then, circling around.”

“No, more like a long coffee break, I think. Ah! Here he comes now. I usually duck inside.”

“And I, at least today, will have to present myself. I have not yet put my name on the letterbox.”

Leaving my new neighbour to his introductions, I went inside and down to the front door. I returned to the balcony just as the postman was escaping Boxer’s friendliness.

“Nothing for you, I guess, eh, Boxer?”

“I expect very little. And you?”

“Bills, it looks like.” I opened the top envelope with a gardening knife that I had stuck in a flowerpot. A small red card fell out and fluttered over to Boxer’s side of the balcony. He picked it up.

” ‘You are warned — ‘ Oh! I say! Sorry, I could not help myself, Charles. Nasty habit I have. Snooping. Is it a prank?”

“Uh – um – yes. A prank, a joke. That’s all.”

“But not the first time, I think. Am I correct?”

“Well, I’ve had a few of these before. How did you guess?”

“The way you reacted. And you opened it first, even though you knew what it was going to be. May I see the envelope, Charles?”

“Here. They’re always the same. Block printing, stamp always crooked, almost — “

“Almost as if signalling someone – somewhere – something. Yes?”

“The postman!”

“Ha ha! No, I think not, Charles. How many of these have you received so far?”

“Seven.”

“Seven! That is quite a lot. And? What do you do?”

“I’ve saved them, but – uh – that’s all. It’s – they’re – uh – just warnings. No threats – yet – no demands — “

“So far. Do they come regularly?”

“I never thought about it. Not on a Saturday, I think, but – hmm. They come with, yes, with the Brückenbauer – that’s Monday.”

“Today is Friday, Charles.”

“So, Mondays and – no, not always or even often on a Friday. I don’t know.”

“B-Post, I see. That allows for a delay to avoid too much regularity. They all go to this postal centre in Härkingen, I think?”

“Where are you from, Boxer? You don’t have a local accent.”

“Not even Bahnhof-tüütsch? No. Of course not. I am from Delémont. That newspaper? Is that the local one? The OT?”

“Yes. Would you like it? I’m through with it.”

“Yes, thank you. We shall speak later, yes, Charles?”

“Of course, Boxer. Of course.”

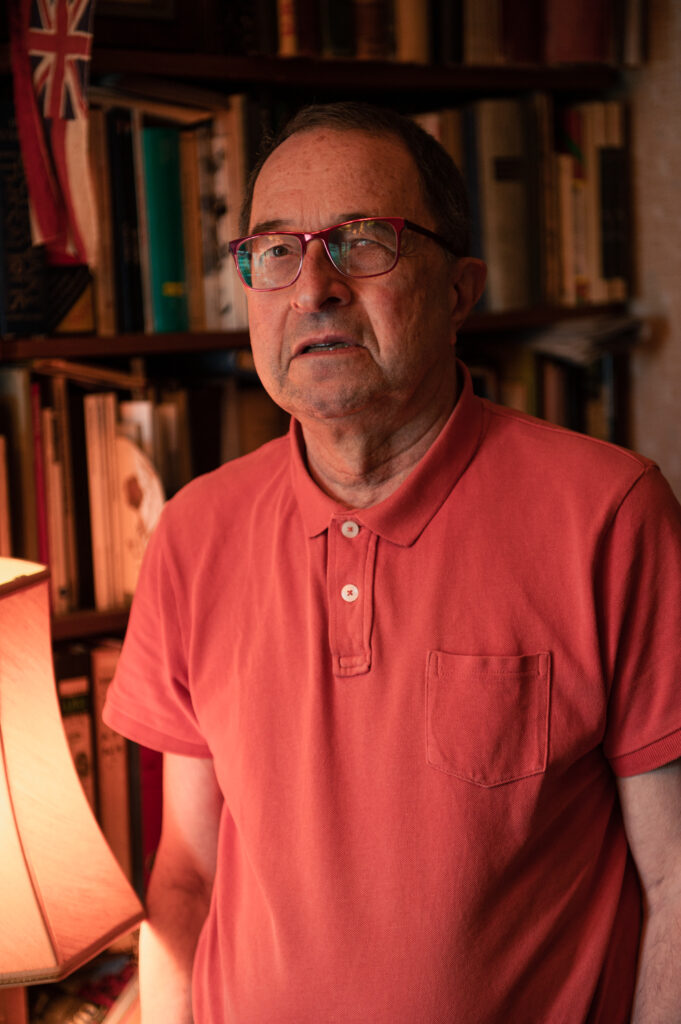

What was it about Boxer that made me trust him – against all my instincts? I knew nothing at all about him, except that he was from Delémont and that he smoked. He was a thin fellow, about my size, weight, age perhaps, as well. His hair was a brilliant black, though, whereas mine was grey mixed with brown. He was not effete but rather gave the air of amused haughtiness tinged lightly with sympathy.

I had assembled my anonymous letters according to date of postmark as far as possible, since some were smudged. They lay on the dining room table. Boxer came over to see the evidence of my postal harassment a few days after his arrival. He spread them out on the table, turning them this way and that like tarot cards. He studied the envelopes and the red cards which each had contained.

“Charles, these were all prepared at the same time, I am sure of it. And the envelopes, as well.”

“Are you a detective?”

“Hardly. Look – you see how over time the writing gets progressively worse? Less precise, more careless, haphazard. The person was getting tired of writing, the hand muscles were weakening. So, done all at once, envelopes addressed, stamped – the author of these notes needed a way to arrange them after sealing the flap.”

“Aha! That’s the positioning of the stamp!”

“Exactly, Charles! Very good. I am guessing that it also signalled, just to the writer, which postal box to drop them in, a different one each time, most likely, to keep it irregular. Something like north, south, right side or left side of the Aare – that sort of indication.”

“But why?”

“The messages all mention or allude to, if I may be so bold as to conclude, an affair which you had several years ago. More recently? Yes. The writer also claims to be a member of the OT staff with access to the online version.”

“I never look at the online edition.”

“That does not matter, Charles. As you said at first, there are no threats, no demands. Yet here is the intent – the author of these messages will put evidence of your affair, such as there might be, online for as long as possible before it gets taken down.”

“No one cares about my affairs. It wasn’t even a local matter. Someone from Lörrach. No one got hurt.”

“So these letters were mailed just over the border, do you think?”

“What? By whom?”

“By the object of your affection in Lörrach, of course.”

“That’s too far-fetched. That’s silly. It was nothing out of the ordinary, this affair, believe me.”

“I do believe you, Charles. That is why I presented two conflicting possibilities just now. Either these were mailed locally or they were not. Your reaction was that they must have been sent locally. I agree.”

“So, Boxer, what do I do?”

“What do WE do, you mean.”

“You shouldn’t get involved.”

“I already am, Charles. No, what we should do is contact the police and the chief editor of the OT. See if they have a cuckoo in their nest.”

Well, I don’t know what Boxer said to the police, but the very next day, the editor at OT rang me. Boxer had already been in touch with the top staff there and wanted a general meeting. I was to be there, in a separate room connected by video monitoring, to observe. Observe what? Boxer was coy. I boldly suggested that he had been rash by confiding in the top staff. What if it was one of them? Boxer laughed off the possibility.

“No, Charles, I think this is too intricate a plan for a newspaper editor to concoct. They are a stalwart bunch, but they prefer simple solutions to simple problems. No, this anonymous letter intrigue smells more like the work of a sub-editor, even a stringer, a freelancer. Someone hired recently, most likely. Everyone will be there tomorrow. Shall we walk there together?”

I’ll never forget Boxer the next day, excited as a monkey given a live hand grenade. I was put into a side office, and I watched on live streaming as the staff, everyone from chief editor to cleaning personnel, lined up outside a large meeting room, with Boxer standing next to the editor.

“Are they all here?”

“Yes, sir! As far as I can tell.”

“Good. That is about twenty. Let the women go in first and ask them to sit at the tables. I will be in when they are all seated.”

The women went in and sat. In front of each was a ballpoint pen and a writing pad. Then Boxer entered.

“Ladies! Thank you for coming. We are conducting a talent search for beautiful, readable handwriting. We would like to get a few sample sentences from each of you. First put your name and section number at the top of the page, then write as I dictate. You may write script or print, as you wish. Are you ready? Write these words: ‘A woman from Olten is an Oltnerin. A man from Olten is an Oltner. But anyone can work for the Oltner Tagblatt.’ Fine! That is it. Just hand in your paper as you leave.”

The women filed out and were replaced by the men, who wrote the same sentences and left. Boxer eagerly went through the writing samples. Naturally I assumed he was comparing the handwriting with that on the messages I had received.

“Damn! It did not work. Your letter writer might still be around, though. I will have to try a different tactic.”

A woman came up to him, wearing a large rain-hood and a heavy coat. It seemed an odd way to dress for a summer shower, I thought, watching to catch sight of her face under the hood. She coughed. Her voice was husky and rough. “Sorry that I’m late. What am I to do?”

She sat and filled out the paper, writing her sentences as dictated, then gave the sheet to Boxer. He looked at the paper, then at her. She had not removed the hood.

“Ma’am, there is a policewoman waiting outside to speak with you, if you would be so kind. Officer Trent, could you come in here, please?”

The officer entered the room, and, as I watched on the video monitor, the woman took down her hood. Astrid! My little Astrid! How could you?

That evening Boxer came over to see me. He was there to console me, I knew, but no consolation could erase the betrayal I felt at that last glimpse I had of my Liebchen.

“Tell me, Boxer, you identified her from the handwriting, didn’t you?”

“Never noticed the handwriting, no.”

“So, what gave her away?”

“A spelling test. A spelling error. Something I had learnt myself only recently. Something a German probably never learns. Even a few Swiss make this mistake.”

“What? Boxer! Tell me!”

“OT is an easy abbreviation. But someone in the know would never, ever write it out in full as Oltener Tagblatt, eh?”

“Boxer – let’s have a drink at the Chöbu, shall we?”

Weiter zum zweiten Teil der Boxer-Literaturkolumne

David Pearce ist ein Schweizer Schriftsteller, wohnt seit 2000 in Olten und hat amerikanische, englische, und französische Wurzeln. Er schreibt auf Englisch Kurzgeschichten, Romane und Theaterstücke.